A self-help manual

Our treatment studies demonstrated that the impediment in natural recovery process caused by helplessness responses could be overcome by simple encouragement for self-exposure in a brief session. These findings implied that the intervention could be as effectively delivered through media other than a therapist (e.g. self-help manuals), provided that the essential elements of therapy are adequately conveyed to survivors. Despite these encouraging results, however, there were some challenges in developing a self-help tool. As is common knowledge to experienced behavior therapists, the most difficult task in exposure treatment is to engage the patient in the idea of exposure to feared situations and ensure compliance with treatment. Indeed, about 30% of patients with anxiety disorders either refuse or drop out from exposure treatment, even when the intervention is delivered by a therapist (Marks, 2002). In some cases, substantial discussion with the client might be necessary to identify and overcome helplessness cognitions, convey self-confidence, and mobilize motivation for change. The interactive nature of the therapist-patient relationship can be of critical importance in such cases. Furthermore, effective explanation of the treatment rationale requires some persuasive discourse, and this is best achieved through personal contact with the person. Unquestioning obedience to the authority of care providers (e.g. “doctor knows what’s best for me”) in some cultures may also facilitate this process. Thus, developing a stand-alone self-help tool that can achieve the same cognitive and motivational impact of one hour of therapist contact poses a major challenge. This might indeed explain in part why stand-alone self-help tools for anxiety disorders are extremely rare (Newman et al., 2003). It might also explain two failed attempts (Ehlers et al., 2003; Scholes et al., 2007) to demonstrate the usefulness of self-help in PTSD.

Our treatment studies demonstrated that the impediment in natural recovery process caused by helplessness responses could be overcome by simple encouragement for self-exposure in a brief session. These findings implied that the intervention could be as effectively delivered through media other than a therapist (e.g. self-help manuals), provided that the essential elements of therapy are adequately conveyed to survivors. Despite these encouraging results, however, there were some challenges in developing a self-help tool. As is common knowledge to experienced behavior therapists, the most difficult task in exposure treatment is to engage the patient in the idea of exposure to feared situations and ensure compliance with treatment. Indeed, about 30% of patients with anxiety disorders either refuse or drop out from exposure treatment, even when the intervention is delivered by a therapist (Marks, 2002). In some cases, substantial discussion with the client might be necessary to identify and overcome helplessness cognitions, convey self-confidence, and mobilize motivation for change. The interactive nature of the therapist-patient relationship can be of critical importance in such cases. Furthermore, effective explanation of the treatment rationale requires some persuasive discourse, and this is best achieved through personal contact with the person. Unquestioning obedience to the authority of care providers (e.g. “doctor knows what’s best for me”) in some cultures may also facilitate this process. Thus, developing a stand-alone self-help tool that can achieve the same cognitive and motivational impact of one hour of therapist contact poses a major challenge. This might indeed explain in part why stand-alone self-help tools for anxiety disorders are extremely rare (Newman et al., 2003). It might also explain two failed attempts (Ehlers et al., 2003; Scholes et al., 2007) to demonstrate the usefulness of self-help in PTSD.

We have explored this issue by developing a highly structured self-help manual that closely paralleled the treatment program used in Study 1. The first version consisted of six sections providing information on (1) PTSD and depression symptoms, (2) self-assessment using a Traumatic Stress Symptom Checklist (TSSC) developed for screening and assessment purposes (Başoğlu et la, 2001), (3) principles of treatment and suitability for treatment, (4) self-assessment of fear and avoidance behaviors using a Fear and Avoidance Questionnaire (FAQ) and instructions on how to define exposure tasks, (5) administering self-exposure sessions, blocking cognitive or behavioral avoidance or distraction strategies, coping with anxiety, panic or flashbacks, monitoring fear cues, and dealing with problems encountered during the first week of treatment, and (6) evaluating progress in treatment, defining new exposure tasks, and dealing with problems encountered during the subsequent weeks of treatment. The highly structured nature of the manual allowed its use as a ‘stand-alone’ treatment tool with minimal or no therapist contact.

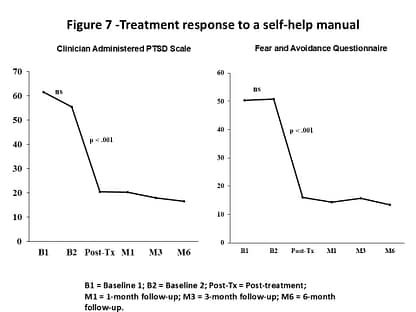

Although we did not have an opportunity to test the manual in a randomized controlled study, we conducted a series of 8 single-case experimental studies to examine whether the manual effectively delivered the treatment rationale, instigated self-exposure, and provided sufficient guidance throughout the treatment among survivors who read it. The study design included two baseline assessments separated by one month of waiting period, followed by the delivery of the manual. Post-treatment assessment was at week 10 and subsequent follow-ups were at 1-, 3-, and 6 months post-treatment. The mean CAPS and FAQ scores before and after treatment are shown in Figure 7.

Although we did not have an opportunity to test the manual in a randomized controlled study, we conducted a series of 8 single-case experimental studies to examine whether the manual effectively delivered the treatment rationale, instigated self-exposure, and provided sufficient guidance throughout the treatment among survivors who read it. The study design included two baseline assessments separated by one month of waiting period, followed by the delivery of the manual. Post-treatment assessment was at week 10 and subsequent follow-ups were at 1-, 3-, and 6 months post-treatment. The mean CAPS and FAQ scores before and after treatment are shown in Figure 7.

The Clinician Administered PTSD Scale (CAPS) scores showed only mean 10% improvement during the baseline period, which was not significant. This is similar to the improvement rates we observed during the 6 and 8 weeks of waiting periods in our controlled studies reviewed earlier. It is also worth noting that this study was conducted 4.5 years after the earthquake with survivors who had chronic PTSD. A substantial reduction was noted in all ratings from the second baseline to post-treatment, ranging from 63% to 73%. Treatment effects were significant on all measures, with effect sizes at the last assessment on the CAPS (Cohen’s d = 2.12), FAQ (Cohen’s d = 2.62), and Work and Social Adjustment Scale (Cohen’s d = 2.65) comparable to those achieved by therapist-delivered treatment (see Table 1). About 70% reduction was noted in behavioral avoidance and PTSD symptoms, with 91% improvement in work, social, and family adjustment. Using the criterion (Jacobson & Truax, 1991) of 2 SD or more improvement since baseline, 7 (88%) cases showed improvement in PTSD. At the same assessment 7 (88%) cases achieved good end-state functioning, which was defined as a CAPS total score of 19 or less indicating absence of PTSD (Weathers et al., 2001). This study suggested that the manual could be a useful means of delivering treatment after an initial assessment.

Can the manual be helpful without any contact with a therapist? When disseminated to survivors, the usefulness of a self-help manual needs to be judged according to two criteria: their effectiveness rate (proportion of improved users among those who read the manual and comply with treatment instructions) and their benefit rate (proportion of improved cases among those who receive the manual). Effectiveness rate is an indication of whether the intervention involves therapeutic elements and how successfully the manual delivers these elements to users, whereas benefit rate reflects not only the effectiveness of the manual but also the probability of it being read and utilized by the targeted survivor population when made available to them. We examined earthquake survivors’ responses to the manual in a pilot study (Başoğlu, unpublished data) involving 84 survivors with PTSD who had taken part in an epidemiological study (Başoğlu et al., 2004). The manual was delivered by students to the survivors’ homes with a brief information leaflet explaining its purpose (but not its content). A phone interview three months later found that 46 (55%) survivors read the manual, 36 (78%) found the treatment credible, and 22 (48%) complied with treatment instructions. Among the latter cases, 17 (77%) rated the manual as fairly to very satisfactory and 20 (91%) as recommendable to others and 19 (86%) rated themselves as improved on a global improvement scale, while 3 (13%) reported no change. Also worth noting is the fact that 35% of 20 survivors who found it recommendable to others actually gave copies of the manual to their friends and neighbors. Improvement did not significantly correlate with any demographic, trauma, or personal history characteristic. Among the 38 survivors who never read the manual, the reasons stated were ‘did not have time’ or ‘neglected it’ in 20 (61%), ‘reminded me of the earthquake’ in 2 (6%), ‘interfering life events’ in 3 (8%), ‘lost the manual’ in 3 (8%), ‘concentration problems or reading difficulty’ in 2 (6%), ‘no problem with fear’ in 1 (3%), and ‘treatment with a booklet not possible’ in 1 (3%)(data missing on 5 cases). Among the 24 survivors who read the manual but did not instigate self-exposure, the stated reasons were ‘did not have time’ in 6 (25%), ‘treatment not convincing’ in 5 (21%), ‘prefer treatment by a therapist’ in 4 (17%), ‘no problem with fear’ in 2 (8%), ‘treatment likely to increase fear’ in 2 (8%), and others (not interested, treatment not relevant to grief problem, did not read entire booklet) in 3 (1%); data were missing on 2 cases. These findings suggest that in most cases the idea of a self-help treatment does not conflict with traditional expectations of treatment from a medical professional. Furthermore, the fact that neither reading the manual nor compliance with it related to age, gender, marital status, education, and intensity of exposure to trauma suggests these factors are not likely to influence its utilization rate.

These results suggest an effectiveness rate of 86% (19 improved cases among 22 treatment compliers) and a benefit rate of 23% (19 improved cases among 84 that received the manual). While this benefit rate may appear relatively low, its implications are better appreciated when extrapolated to tens or hundreds of thousands of survivors. It means that nearly 1 in 4 cases can be helped by simply distributing the manual in the community without any therapist contact. This proportion can be increased further by various means. For example, in outreach programs targeting survivor shelters or camps, the manual can be distributed to groups of survivors after a brief presentation and encouragement from a health professional or camp administrator. Furthermore, it can be distributed in the community with some media campaigning designed to encourage its use.

It is also worth noting that the pilot study findings pertain to the first version of the manual, which was later shortened and streamlined for easier readability and also revised in other ways to maximize its impact. The second version does not include a section with information on PTSD and depression symptoms but includes a section on treatment on prolonged grief. Thus, psychoeducation is no longer part of CFBT. We know from experience that the assessment instruments routinely used in treatment, such as the TSSC, FAQ, and Depression Rating Scale, convey sufficient information to survivors about the manifestations of traumatic stress and depressive symptoms.

Our experience suggests that self-treatment does not pose any serious risks to survivors. The manual provides emphatic instructions to contact mental healthcare providers in case of problems during treatment, such as suicidal ideas, uncontrollable rage, behavior harmful to self or others, and unmanageable panics or flashbacks. The first version of the manual instructed the survivors to contact our regional community center in case of problems. In the pilot study none of the survivors contacted us during the study period and no adverse effects were reported at the phone interview. The manual was later distributed to about 900 survivors in the disaster region and none reported any problems.

Despite the preliminary nature of evidence regarding the usefulness of the self-help manual, we believe it has much potential as a treatment dissemination tool. Evidence at least suggests that the critical ingredient of the intervention is the content of the message delivered, rather than the medium of delivery. Its effectiveness could be attributed in part to its trauma-specific and highly structured content that closely parallels therapist-delivered treatment. Indeed, a survivor noted that it makes one feel as if one is getting treatment from an invisible therapist. The usefulness of self-help approach is hardly surprising in view of our observations of natural recovery in many cases through self-instigated exposure without any contact with a therapist.

The usefulness of the manual might be viewed as limited in post-disaster settings where there is a high rate of illiteracy or where people are lacking in reading habits. The latter has indeed been a problem in our work, particularly with survivors of lower socio-educational background. This does not, however, pose a serious problem for an outreach program when alternative methods of treatment delivery (e.g. single-session treatments) are available. The problem posed by illiteracy could also be overcome to some extent by recruiting help from family members, relatives, or friends who can act as lay therapists by reading the manual to the survivor and encourage its utilization, or even deliver the treatment with the help of a highly structured Treatment Delivery Manual we have developed just for this purpose. In addition, audio (or video) versions of the manual could be developed and used in regions where there is at least electricity (or battery-run play-back instruments).

In the aftermath of a disaster there may be occasions where a self-help manual might be the only conceivable form of psychological help for survivors, at least for some time. For example, there may be remote and difficult-to-access regions of the country where no form of psychological help is ever likely to reach. Printed or audio versions of the manual might be considered for such locations. Furthermore, self-help may be the only viable option in delivering psychological care to large numbers of survivors in the early aftermath of mass trauma events (e.g. first few months). Indeed, this is the stage when conditioned fear responses develop and generalize to a wide range of situations. Informing survivors about how to deal with fear at this stage might prevent chronic traumatic stress in the longer term. As noted earlier, evidence of CFBT efficacy comes in part from studies conducted at a time when the aftershocks were continuing. Because of widespread fear caused by aftershocks, this is also the stage when demands for help from survivors are likely to be most intense. In such circumstances, the self-help manual might be the only feasible option in meeting their demands.

Self-help tools are also needed in the post-trauma phase. Although mass trauma events initially trigger a remarkable media and public response, with aid and resources pouring in, the sad reality is that such interest rapidly fades away. As the disaster begins to disappear from media headlines, local and national governments (as well as the international community) are often more than willing to forget about the survivors. As time goes by, these factors make it increasingly difficult to find funding for outreach programs, no matter how cost-effective they might be. In such circumstances, self-help remains as the only option in delivering care to survivors.

References

Başoğlu M, Şalcıoğlu E, Livanou M et al (2001) A Study of the Validity of a Screening Instrument for Traumatic Stress in Earthquake Survivors in Turkey. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 14: 491-509.

Başoğlu M, Kilic C, Şalcıoğlu E, Livanou M (2004) Prevalence of posttraumatic stress disorder and comorbid depression in earthquake survivors in Turkey: An epidemiological study. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 17(2):133-141.

Ehlers, A., Clark, D. M., Hackmann, A., Mcmanus, F., Fennell, M., Herbert, C. & Mayou, R. (2003). A randomized controlled trial of cognitive therapy, a self-help booklet, and repeated assessments as early interventions for posttraumatic stress disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry, 60, 1024-1032.

Jacobson, N. S. & Truax, P. (1991). Clinical significance: a statistical approach to defining meaningful change in psychotherapy research. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 59, 12-19.

Marks, I. M. (2002). The maturing of therapy: Some brief psychotherapies help anxiety/depressive disorders but mechanisms of action are unclear. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 180, 200-204.

Newman, M. G., Erickson, T., Przeworski, A. & Dzus, E. (2003). Self-help and minimal contact therapies for anxiety disorders: Is human contact necessary for therapeutic efficacy? Journal of Clinical Psychology, 59.

Scholes, C., Turpin, G. & Mason, S. (2007). A randomised controlled trial to assess the effectiveness of providing self-help information to people with symptoms of acute stress disorder following a traumatic injury. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 45, 2527-2536.

Weathers, F. W., Keane, T. M. & Davidson, J. R. T. (2001). Clinician-administered PTSD scale: A review of the first ten years of research. Depression and Anxiety, 13, 132-156.